by Augusto Corrieri

If attention was an experiment in living, rather than a deal or a calculation. – Adam Phillips

1. magic

One thing that magic and magicians can teach us about distraction is that it isn’t what we think it is.

A fairly common assumption or trope regarding magic involves the magician forcibly pointing away from the stage, towards somewhere else in the theatre – the hackneyed ‘Look over there!’ – so as to presumably carry out the trickery undetected.

It’s easy to see how, in the context of a magic show, this type of distraction cannot succeed, as the audience would surely detect the ruse: upon turning back to look at the stage, discovering that a certain object has now appeared, or now vanished, or now transformed, spectators would surely protest: ‘You distracted us, it doesn’t count; do it again, without distracting us.’

To really succeed, then, the distraction must never be perceived as such. And for that to happen, audiences need to always experience a degree of real “freedom”: the freedom to look wherever they please, whenever they please. Spectators need to be satisfied that their inquisitive and attentional capacities are not being restricted, so that, when an object does inexplicably vanish, appear, transform, etc., they will then experience the illusion of impossibility, aka magic – “I was looking at her hands all the time, and then suddenly the cards all went blank!”

Before any magic can happen, the magician must convince the audience that no distraction is occurring, or could possibly occur. Hence the reason magicians tend to rely on expressions such as ‘Look’, ‘Watch closely’, ‘Please examine this pack of cards’, or even ‘I’ll do it again, this time as slowly as possible’… We, the audience, know distraction is happening somewhere, at some point, but for all our looking, we cannot find any evidence of having been distracted; after all, we were looking the whole time.

What magic teaches us, experientially, is that focused attention and distraction are not mutually exclusive, or even different things. In fact, it is the way we pay close attention – in an attempt to discern the secret method – that allows distraction to take place.

Graffiti idea:

DECEPTION IS WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU’RE TOO BUSY TRYING TO FIND OUT HOW IT’S DONE

2. productivity

After over a decade of practising meditation (and I mean the word “practise” in the pragmatic sense of doing it every day, even when not in the mood, convinced by all the books to make it part of my daily routine, so as to not forget to do it), I am now taking a break.

Meditation seems to have become another habit or pattern – distractedly reaching for the meditation stool, distractedly sitting, distractedly starting the 10-minute timer, distractedly noticing thoughts come and go. The act of meditating seems to have acquired the same character as the mindless routines of everyday life, the same routines that meditation might have revitalised or rendered strange and quietly compelling. The shacking off has itself become part of the torpor.

It hasn’t always been so.

During past meditation sessions, I have at times experienced a strange modification, a mode of consciousness poised between absorption and distraction: I think this is what is referred to as choiceless awareness, a mode of attention where any thought or sensation experienced can unfold, without pulling or dominating consciousness, and without an “I” in charge of choosing what to focus on.

Another term for it might be ‘lantern consciousness’; in discussing the psychotropic effects of caffeine and its histories, Michael Pollan refers to two forms of attention, or consciousness, each linked to modes of theatrical lighting, the spotlight and the lantern:

Cognitive psychologists sometimes talk in terms of two distinct types of consciousness: spotlight consciousness, which illuminates a single focal point of attention, making it very good for reasoning, and lantern consciousness, in which attention is less focused yet illuminates a broader field of attention. Young children tend to exhibit lantern consciousness; so do many people on psychedelics. This more diffuse form of attention lends itself to mind wandering, free association, and the making of novel connections – all of which can nourish creativity. By comparison, caffeine’s big contribution to human progress has been to intensify spotlight consciousness – the focused, linear, abstract and efficient cognitive processing more closely associated with mental work than play. This, more than anything else, is what made caffeine the perfect drug not only for the age of reason and the Enlightenment, but for the rise of capitalism, too.

It is the lantern consciousness described by Pollan that chimes with the choiceless awareness of meditation.

And, while I can’t be sure of this, I suspect this form of attention is rather impervious to distraction: not because of some ascetic uber-presence or total control (‘nothing can distract me!’), but rather the very opposite: a grounded acceptance that anything that happens is what is happening; the most harrowing thought, the loudest sound, or a gentle breeze felt on the arm: not one of these is distracting, since there is nothing to distract from.

Is distraction, then, really just a feature (and a “problem”), of the goal-oriented focused type of attention that, as Pollen writes, characterises capitalist production?

Graffiti idea:

PRODUCTIVITY = THE COLONIZATION OF THE SELF

3. Kate Zambreno’s Drifts

“What prevents a book from being written becomes the book” – found in my notebook, citing the notebooks of Camus, who was himself quoting Marcus Aurelius.

US writer Kate Zambreno’s Drifts, published in 2020, is billed as a novel, though a more accurate description might be something like autofictional diary. The first person narrator, a writer called Kate Zambreno, provides diaristic entries about relatively mundane aspects of her day – the dog, the neighbours, life as an adjunct professor – as well as an ongoing biographical account of the poet Rilke, and, crucially, a sense of foreboding and inadequacy in trying to write a book called Drifts.

What prevents me from writing the book? The heat, the dog, the day, air-conditioning, desiring to exist in the present tense, constant thinking, sickness, fucking, groceries, cooking, yoga, loneliness and sadness, the internet, late capitalism, binge-watching television on my computer, competition and jealousy over the attention of other writers, confusion over the novel, circling around but not finishing anything, reading, researching, masturbating, time passing. / A fluorescent green Post-it note is on my laptop when I return from a walk: “How to fold time into a book?”

Zambreno skirts close to but avoids the self-reflexive postmodern conceit; instead, her book (about the struggle to write her book) functions as a kind of slowly cumulative celebration of the ‘not yet but’: it is a eulogy of notebooks, note-taking, books obsessed over, books left unread, postponing the ‘work’, a dreamlike unproductivity, all underlined by the struggle to inhabit an artlife amid the daily everythings.

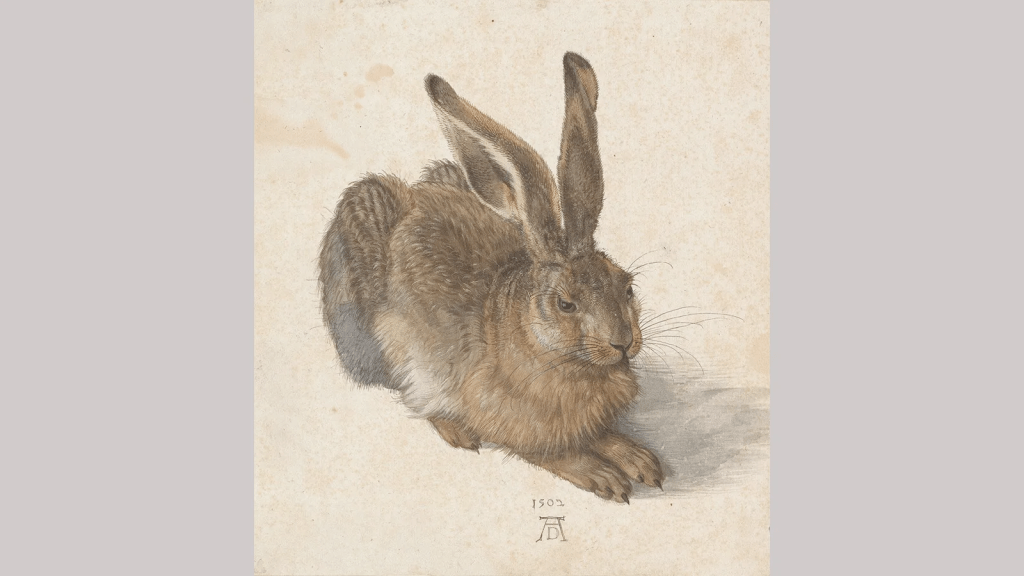

She returns again and again to a few canonical figures (Sontag, Dürer, Wittgenstein), not to build up a clear study or argument, but rather because so much intellectual work is partly about returning to passages and works, over and over again, even when this activity doesn’t really yield anything “new” (I am reminded of the hours I have spent walking around bookshops and libraries, endlessly re-revisiting the names of authors and the titles of books I knew, or thought I knew, as though retracing some private constellation).

At other times, what is foregrounded is writerly doubt, or the inability to capture anything:

I never know, when I sit down to write, how to replicate that movement and those discoveries that come when my mind wanders.

Which is akin to asking about the relationship between form and the unformed, production and potential:

the madness of writing versus the madness of not writing.

Damned either way, the form of the journal, and its endless appeal to the unfinished, the provisional, allows a peculiar attentional shift: the drift, or a desire for drift. The notebookish accumulation of seemingly trivial daily occurrences begins to acquire a strange consistency, and all the half-attempts, questions and misfires, in the end, really do take us there. In place of The Manuscript, there is this life of distraction, and the days piling high, all lived in the exalted orbit of the possibility of writing.

Graffiti idea:

BE THE DISTRACTION YOU WANT TO SEE

Sources

Adam Phillips (2019), Attention Seeking (Milton Keynes: Penguin Random House)

Michael Pollan (2021), This Is Your Mind on Plants (New York: Penguin Press)

Kate Zambreno (2020), Drifts (New York: Riverhead Books)

Augusto Corrieri is a writer and performance maker with an interest in ecology and perception.

His book In Place Of a Show: What Happens Inside Theatres When Nothing Is Happening (2016) is published by Bloomsbury Methuen Drama.

He also presents sleight-of-hand magic performances under the pseudonym Vincent Gambini, and lectures in Theatre & Performance at the University of Sussex.