by Susan Rudy

.

A generation of us grew up hearing, from our fathers and their proxies, that we would not have to be like our mothers.

.

Are you, asked Alison Bechdel, my mother?

.

Back there, I am a woman; here, I am not so sure.

.

Consider that gender is acquired at least in part through the repudiation of homosexual attachments.

.

Do I have a child, or not?

.

Even after I come out, I am, still, a mother.

.

Gender is susceptible to extraordinary change; gender inequality is, by comparison, much more durable.

.

I am afraid of turning out like my mother.

.

I am not not a mother.

.

I am their mother.

.

I don’t want to be a single mother.

.

I don’t want to live alone.

.

I don’t want to lose my daughters.

.

I don’t want to pay for everything.

.

I had found a loving, caring, nurturing father for them.

.

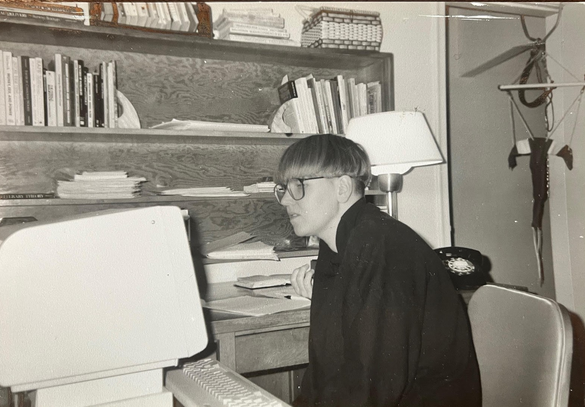

I look at the photo of me, 3 weeks postpartum, at my desk in 1990, and consider writing a piece called ‘Judith Butler, the jolly jumper and me’.

.

I thought I had been a good enough mother.

.

I want pleasure and joy and intellectual challenge.

.

I want security, love, and comfort.

.

I want to be in charge of my life.

.

I was always biting my nails, sitting with my legs wide open, and stomping around the house.

.

I was queer as a mother.

.

I was the mother who could not mother.

.

I’m making their dinner.

.

I’m not selfless enough to be a mother.

.

I’ve always had a life apart from being their mother.

.

I’ve done my work as a mother.

.

If my mother had had the words, she would have called me a very queer girl.

.

Is gender hegemony elastic, really?

.

Is the space between mother and child really intersubjective, Jessica Benjamin?

.

It’s like having my mother around, the house is so tidy.

.

Jill is the virtuous mother that Ritchie needed when his biological mother was insufficient.

.

Like any mother role on television, Jill doesn’t exist outside of it.

.

Love that doesn’t need love in return, love that doesn’t ask for anything, love that knows what love is, love that never doubts, love that knows pain is nothing, that pain has nothing to do with it, that it’s futile, that violence is always about the person inflicting it.

.

Maternity leave as a leave from maternity: is this thinkable?

.

Mother, as a status, an identity, a form of power, a lack of power, a position, dominated, and dominant, victim and persecutor, it doesn’t exist.

.

My ‘maiden aunts’, as my mother called them, were not, as far as I knew, mothers.

.

My mother is intelligent, self-reliant, resilient, cold. And so am I.

.

On maternity leave, all I wanted to do was read, eat, and watch tv.

.

Perhaps I am, still, on leave from maternity, or wishing to be.

.

She did not know what her mother looked like; she went right by her; she did not see her.

.

She does mostly as she pleases and makes a lot of money.

.

She is not a mother.

.

She may not be a ‘she’.

.

She sees me, all grandmotherly and motherly and queer.

.

The closure of wartime nurseries also had to do with many other ideological formations, most notably those surrounding the ‘mother’ as a separate entity from the woman worker.

.

The girl becomes a girl by being subject to a prohibition that bars the mother as an object of desire and installs that barred object as a part of the ego, indeed, as a melancholic identification.

.

There have been good reasons for doing what I have done: keeping the mother part of me separate from the intellectual part of me allowed me to have an intellectual self.

.

There is no such thing as a mother.

.

There is so little space to think about love and mothering.

.

There’s only love, which is completely different.

.

These roles haunt me, live in me, won’t leave me alone.

.

To have been just a mother would not have been enough.

.

We don’t see any of Jill’s life after Ritchie’s death, because why would we care enough about a Black female character to have an episode that fully revolves around her life?

.

We would not have to be like our mothers, would we?

.

What does that question even mean, and who would ask it?

.

What if there aren’t any women, what then?

.

What is she being asked to do when they beg her, come home and be a mother again.

.

What kind of a mother are you?

.

When Ritchie’s story ends, so does Jill’s.

.

When the married woman standing (with her husband) in front of her introduced herself, she saw a lesbian.

.

Whether I was their mother was a question almost everyone but me was asking.

.

While Alison Bechdel was being a dyke to watch out for in the 1980s, I was having babies, finishing my PhD, and feeling scared of how drawn I felt to my (lesbian?) colleagues.

.

Who would we have to be?

*

.

Sentence Sources

Note: ‘Judith Butler, the jolly jumper, and me’ was created out of an alphabetised list of sentences selected in early 2024 out of an archive of materials collected over a seven-year period for an abandoned memoir project. Materials in the archive included early drafts, research notes (including quotations) on more than 500 theoretical texts, journal entries, interviews, quotations from articles, books, films, and television shows. A book-length version of this piece, entitled Hand Over, is in progress.

Are you, asked Alison Bechdel, my mother? In 2012, Alison Bechdel published a book called Are you my mother? This is also the title of a children’s book by P.D. Eastman published the year before I was born, on 12 June 1960.

Consider that gender is acquired: Butler, ‘Melancholy Gender’, Psychoanalytic Dialogues (1995): 169.

Do I have a child, or not? Sheila Heti in conversation with Sally Rooney, 2018.

Gender is susceptible to extraordinary change: Bridges and Pascoe, ‘On the elasticity of gender hegemony’, in Gender Reckonings, eds. Messerschmidt et al, 2018.

Is the space between mother and child really intersubjective, Jessica Benjamin? In The Bonds of Love, Benjamin argues that in the mother-child bond we find an experience of ‘recognition’ that ‘entails the paradox that “you” who are “mine” are also different, new, outside of me’, yet this experience is from the perspective of the mother. Like the child, in Are you my mother?, who cannot see his mother when she is right in front of him, we cannot see the bond we have with a mother who does not see us.

Jill is the virtuous mother that Ritchie needed when his biological mother was insufficient: Sterk, ‘Jill and the female carer’, The F Word (2021)

Like any mother role on television, Jill doesn’t exist out of it: Sterk, ‘Jill and the female carer’, The F Word (2021).

Love that doesn’t need love in return, love that doesn’t ask for anything: Debré, Love Me Tender (2020): 99.

Mother, as a status, an identity, a form of power, a lack of power: Debré, Love Me Tender (2020): 99.

She did not know what her mother looked like: paraphrase of Eastman, 1960.

The closure of wartime nurseries also had to do with many other ideological formations, most notably those surrounding the ‘mother’ as a separate entity from the woman worker: Riley, ‘Does a sex have a history?’ New Formations (1987): 44.

The girl becomes a girl by being subject to a prohibition: Butler, ‘Melancholy Gender’, Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 1995: 169

There is no such thing as a mother: Debré, Love Me Tender (2020): 99.

There’s only love, which is completely different: Debré, Love Me Tender (2020): 99.

We don’t see any of her life after Ritchie’s death, because why would we care enough about a Black female character to have an episode that fully revolves around her life: Sterk, ‘Jill and the female carer’, The F Word (2021).

What is she being asked to do: Notes on television series, Come Home, BBC One, March 2018; see also ‘New BBC drama Come Home, tackles the taboo of parenting’, The Northern Echo (22 March 2018).

When Ritchie’s story ends, so does Jill’s: Sterk, ‘Jill and the female carer’, The F Word (2021). Sterk’s article was written in response to Russell T. Davies’ television drama series It’s a Sin, which is set in London in the 1980s and depicts the lives of a group of gay men. Through her focus on Jill, Sterk provides an ode to the caregivers of the AIDS epidemic, but her aim is to critique the idealisation of care represented in the series.

.

*

.

Works Cited

Bechdel, Alison, Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama (London: Jonathan Cape, 2012).

Benjamin, Jessica, The Bonds of Love: Psychoanalysis, Feminism and the Problem of Domination (New York: Pantheon, 1988).

Bridges, T., and C.J. Pascal, ‘On the elasticity of gender hegemony: Why hybrid masculinities fail to undermine gender and sexual inequality’, in Messerschmidt et al, 254-274.

Butler, Judith, ‘Melancholy Gender – Refused Identification’, Psychoanalytic Dialogues Vol. 5, No. 2 (1995): 165-180.

Come Home, BBC One [television series], March 2018.

Debré, Constance, Love Me Tender, trans. Holly James (Paris: Flammarion, 2020).

Eastman, P.D. Are You My Mother? (New York: Harper Collins, 1960).

Heti, Sheila and Sally Rooney. ‘Motherhood: Sheila Heti and Sally Rooney.’ London Review Bookshop. 24 May 2018. 7 pm. 49 minutes.

Messerschmidt, J.W., P.Y. Martin, M.A. Messner, and R. Connell, eds., Gender Reckonings: New Social Theory and Research (New York: New York University Press, 2018).

Sterk, Pippa, ‘Jill and the female carer’, The F Word: Contemporary UK Feminism, 8 February 2021.

*

Susan Rudy is a London-based queer poet, feminist critic, writer, editor, and teacher whose work focusses on what experimental writing can teach us about gender. Work in progress includes Hand Over, a poetic and experimental work of creative non-fiction about queerness and motherhood. In 2024, Susan’s creative practice was supported by a six-week Leighton Artists’ Studio Residency at Canada’s Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity.